Germany’s Approach to the Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Bureaucracy Versus Strategy

Share

In the piece entitled “How Not To Approach Foreign Policy,” we considered the causes and impact of regressing government performance on foreign affairs, considering factors like institutional rigidity, organizational inertia, and lack of adaptability. We examined how these factors affect strategic decision-making at both institutional and governmental levels, along with their implications for long-term global positioning. One of the key concepts addressed in that piece was the progressive nature of the failures, and how they followed the parable of the frog in the water, the gradual increase in temperature is imperceptible until it is too late.

To illustrate how these concepts apply in practice, we will look at how they manifest in the real world. There is no shortage of examples of decision making by governments and politicians on the international arena, but to drive home the point that the factors covered in the abovementioned piece are universally applicable, I selected Germany as an example becasue it is a government that is renowned for its efficiency, effectiveness, and resources.

We will consider the case of Germany’s foreign policy approach leading up to and during the early stages of the Russo-Ukrainian war. The German government is well-resourced, consistently placing in the top ten in transparency indices and has an extensive global reach with over 200 diplomatic missions abroad. It has a solid foundation and background in global policy, is an important actor in European affairs, has a prominent global role, and significant international influence through its extensive cooperation with actors both governmental and intergovernmental. An economic powerhouse, Germany’s reach is one of the most expansive in the world, connecting it to all corners of the globe through investment and trade. German institutions, distinguished by their methodical approaches and strong organizational bases, form a solid foundation for a foreign policy apparatus that works together like a well-oiled machine.

German Foreign Policy

To contextualize the issue, it is worth highlighting the significance of Germany’s accomplishments on the international arena. In the post WWII era, defeated and all but razed to the ground, Germany managed to reposition itself politically and economically over the span of a few decades into an economic and political fulcrum in Europe and beyond. Through capacity building, institutional development, and investment in education, it leveraged its resources and established a prominent global presence on the economic and political fronts, and navigated its way to leadership roles in multilateral organizations and regional blocs.

These accomplishments are an example of successful adaptation of a government’s foreign policy approach, responding effectively to changed circumstances, in addition to a proactive approach to international relations. Navigating a complex reunification process in 1990, Germany successfully adapted and worked to advance its interests and forge partnerships and alliances across multiple regions, progressively evolving into one of the most influential actors on the global arena.

These accomplishments serve to remind us of a key point in our case study, namely that previous accomplishments do not ensure future success. This is a government that has consistently shown itself capable of adapting to change, developing strategic policies designed to further its interests, and consolidating its global position. It has exhibited the qualities of dynamism and agility required to navigate massive transitional phases.

Nevertheless, and despite having the tools, knowhow, institutional memory and expertise in its foreign policy apparatus, it appears in our example to have succumbed to the siren calls of complacency, rigidity and bureaucratic inertia. Rather than the paragon of adaptability and versatility, symptoms of stagnation manifested in one of the most strategically significant moments for Germany.

The European Context

It is nearing the end of 2021, and in the wake of the COVID pandemic the world is in a state of recovery. There is intensification of dialogue in northern and eastern Europe on defense, with wide participation and mention of possible expansions of NATO membership to include Sweden and Finland. Russia’s escalating position on Ukraine is gaining traction and the cycle of events seems inevitably headed towards conflict. The US administration intensifies its communications of a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine, sharing intelligence with its European allies including Germany pointing towards this potentiality. As a result of these intensified diplomatic efforts, Berlin, among other European capitals, aligned its approach to Russia with that of the US; rather than focusing on de-escalation, the trajectory shifted to a considerably more aggressive tone.

Meanwhile, the construction of Nord Stream 2 was completed, and another step towards Euro Russian economic integration was nearing completion. The natural gas flow from Russia to Germany via the Baltic Sea could have been a milestone for energy cooperation, fostering stability and aligning interests in the region. The potential economic growth spurred by intensified Russo European cooperation could have led to deepening political and strategic cooperation; the pipeline itself is ancillary to the broader potentials of cooperation that it represented, as well as the doors of dialogue it could have encouraged.

The US had voiced reservations about the pipeline, framing it as an opportunity for Russia to wield energy as a weapon against Europe through increased reliance on Russian natural gas, weakening Europe’s resolve in the face of the threats (allegedly) posed by Russia to European stability. It further stressed that Europe could not at the same time expect to use the US and NATO to deter potential Russian threats, while funding the Kremlin through energy revenues.

Over the course of negotiations with the freshly sworn in German government, the US managed to convince Germany to include the pipeline within possible sanctions programs against Russia. With Europe and Germany firmly aligned with the US position on Russia, with each side entrenching their position, the situation escalated and reached an impasse, resulting in the beginning of the Russian offensive on Ukraine in February 2022. The rest, quite literally, is history.

The Freshly Appointed German Government

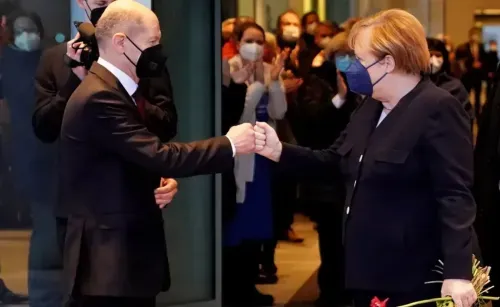

Amidst this backdrop of complex international dynamics, the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was sworn in and formed his government on 8 December 2021, deep into the tensions between Russia, Europe and NATO. With a new Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs and a new Federal Minister of Defense, the newly formed government was baptized by fire in the international arena. It began its international mandate in the eye of the brewing European storm.

Even if we grant that German government agencies have strong institutional memories and do not rely on single individuals to direct their strategic directions, the situation remained complicated. The newly appointed ministers appointed new leadership teams, and therefore their institutions were navigating not only a complicated international situation, but transitioning internally as well.

Therefore, we observe a newly formed government facing an international crisis of monumental proportions, and under internal and international pressure to take a position and formulate a strategy to deal with the looming predicament. Robust as German institutions may be, transitional periods of adjustment shift the focus from substantive matters to organizational ones. With these variables in play, it is entirely probable that the German foreign policy apparatus was not positioned to operate at its full potential.

A Fistful of Errors

It is rarely one decision that causes a lapse in the strategic direction of an organization or government, rather it is more often than not a collection of factors that cumulatively regress an organization’s performance; like no single snowflake feels responsible for the avalanche, no single factor alone is to blame for an institutional failure.

Under stress, a common psychological phenomenon is to regress to familiar and heuristic approaches to problem solving, painting the world in black and white tones. In essence, persons facing stressful situations tend to adopt mental shortcuts and apply generalizations to reduce cognitive loads on already strained nervous systems (for more on this concept read 'Thinking, Fast and Slow'). The relevance of this phenomenon to our case is that the newly appointed ministers and their newly appointed leadership teams found themselves deep in the fires of a crisis of global implications, while navigating an already complex transitional period of adaptation to their new positions.

It is not entirely surprising therefore that decisions made during this time seemed to reflect almost automatic responses to external stimuli. The ministers in their new roles, not yet fully accustomed to their new responsibilities nor the organizations that they were now heading, had to rely on rapid absorption of unfamiliar (and incredibly complex) topics and organizational nuances. Falling back on what was familiar, and leaning on the bureaucratic inertia of their institutions, their decisions were influenced by deadlines, external factors, high stakes and unfamiliarity.

With the looming threat of Russia to the east, the pressure from the US, and European governments looking to Germany for leadership, the onus was on the German government to take a swift decision on positioning.

Under these pressures, the new leadership appears to have opted to simplify the complex situation in the interest of rapid decision making. In framing the scenario in terms of black and white, it became easier to comprehend; the US is our ally and therefore our interests align, while Russia is not our ally and therefore our interests conflict.

By apprently adopting this approach, Germany may have allowed its foreign policy decisions to be guided by US regional interests rather than its own. The foreign policy apparatus seems to have disregarded from its consideration the untapped potentials of alternative approaches to Russia that could have reshaped regional and global power dynamics in favor of Germany through positioning it as a key operator, mediator, facilitator and broker of stability.

It seems apparent that there were voices within the German apparatus that were intent on stalling the war. Germany delayed to the point that questions arose on the impact of its actions on the unity of NATO decisions in facing Russia. Despite the presence of these voices, the resulting decisions seem to have dismissed them.

By operating on precedents that had worked in previous instances (supporting the US position), the German foreign policy apparatus displayed a certain lack of agility, exhibiting instead a rigid adherence to previous behavioral models. Based on those models, and potentially ignoring internal counsel opposing the prevailing direction of thought, German foreign policy leadership steered the ship in a predetermined direction. This decision-making pattern exhibits a possible misjudgment borne out of discounting opposing perspectives.

In late 2021 the EU, still reeling from Brexit that happened the year before, was vulnerable and the internal European dynamics were still being reassessed and redefined. Nevertheless, until 2017 the direction of Europe was to engage with Russia acknowledging their interdependence despite the diverging perspectives. Both the “European Security Strategy” and the “Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy,” published in 2003 and 2017 respectively, acknowledge the challenges posed by Russia while at the same time focusing on engagement and cooperation. The “Strategic Compass For Security and Defense” issued by the EU in March 2022 in the wake of the Russian offensive into Ukraine, appears to be a reactive rather than proactive document, where the European tone shifts considerably concerning Russia in response to the shifting geopolitical considerations on the ground. It aligns with NATO’s strategic concept issued in June of the same year.

In siding with the US position on Russia, Germany’s foreign affairs apparatus, rather than pulling Russia westwards toward Europe, pushed it eastward toward China. This was an entirely predictable outcome based on the information available at the time given that in the face of an implacable Europe, few alternatives remained available to Russia.

With a rigidly inflexible NATO on its western front seemingly intent on expandingly threateningly close to Russia, it decided that the cooperative approach would no longer bear fruit due to the lack of dialogue partners. This geopolitical rift increased the divide between Europe and Russia, which suits NATO’s objectives but not necessarilythose of the EU. In opting to prioritize its NATO role over its European one, it possibly reduced its own role from fulcrum and mediator to that of one among many; rather than shape the developments on the ground, Germany is now forced to react to them.

Germany instead of reigning in the tensions, and prioritizing its own strategic interests of securing a stable and independent European security policy, made the decision to adopt an uncompromising position that closed the doors of cooperation. This is despite the fact that had Germany taken the lead on the European front, it could have realistically gathered support for a European led rather than US led response, particularly with the support of France that had the same inclination.

Had Germany opted to take on the mantle of mediator, with its considerable influence in Europe and on Russia, as well as its ability to operate independently of US and NATO interests, it could have reshaped both its own role and the strategic direction of the EU Common Security and Defense Policy and the European Defense Agency, where it would have had considerably more sway and leverage.

The opportunity costs of this decision by German decision makers could prove considerable, and shed light on the importance of awareness to changing interests, shifting dynamics, and adapting to them. One of the most crucial lost opportunities for Germany is its ability to shape the regional context in which it operates. Its decision to prioritize its NATO role and adopt the organization’s strategic objectives as its own relegated its independent foreign policy on regional security to a secondary role, forced to accommodate the strategic direction of the bloc in lieu of its own geostrategic priorities.

With its role as a supporting actor rather than a primary one, Germany’s interests are of lower concern to Russia, and could potentially continue to diminish as Germany persists in this position. Therefore, not only is its influence reduced, but its interests are becoming less consequential to the major actors; at this stage it is all but taken for granted that Germany will support whatever direction NATO – led by the US- will take. Therefore, and unless the German government takes steps to correct this direction it will fade further into the background in shaping the future of European strategic security.

Causes of These Effects

We have already noted that the German government tasked with addressing this challenge was a newly formed one, with new leaders assuming their roles amidst the evolving chaos. However, that is not enough to account for the decision making process we explored, and diving deeper may help shed light on how even the most well structured and resourced institutions can be vulnerable to challenges.

Even without access to the intraorganizational dynamics in play within the German foreign policy apparatus, we can nevertheless trace our way backwards through the outcomes to attempt to identify the process that led to these decisions.

1. Institutional Resources and Corruption

It was not a question of funding or resources; the Germany Federal Ministry of Foreign Affairs is both well-funded and well-staffed, therefore a shortage of resources could not be blamed for the oversights witnessed over the course of the past three years. Neither could it be a case of rampant corruption chipping away at the foundations of the institution; with one of the lowest corruption indices as highlighted above, this is a highly unlikely cause.

2. Caliber of Staff and Institutional Memory

The German foreign policy apparatus boasts exceptional expertise and know-how, with staff possessing solid educational backgrounds and extensive field experience. There is no lack of knowledge at the individual or organizational levels that would suggest a trend toward repeated errors in assessment, analysis, or understanding of the international dynamics in play.

Is it then a question of institutional memory? Was there not enough of a foundation on the institutional level to navigate a challenge of this magnitude? That seems highly unlikely given the exceptional accomplishments of the German Foreign Office in literally rebuilding its global foreign presence from scratch in the wake of WWII, and then again during the reunification process. It has navigated, with considerable success, challenges of gargantuan proportions.

While the issue of Minister Annalena Baerbock’s lack of diplomatic background and expertise in international relations is noted, it is not uncommon for German officials appointed to this position to come from a variety of different backgrounds. Yet, Germany’s foreign policy accomplishments are significant as alluded to earlier, indicating that the institution is structured to address and overcome the resultant hurdles, dismissing that as a potential cause of the problem.

3. Leadership Influence and Predetermined Outcomes

A potential reason for the decisions made could be that leadership steered institutions toward predetermined outcomes. Under the considerable pressure of the crisis, the newly appointed leaders may have fallen back on familiar behavioral patterns, relying on precedent rather than reassessing the complex, high-stakes situation at hand. As related earlier, this is a common psychological defense mechanism in the face of stressful and complicated situations.

4. Communication Gaps and Organizational Rigidity

Compounding this matter would be the possibility that there may also have been ineffective communication channels within German institutions, preventing alternative opinions from reaching decision-makers. New leadership teams were navigating unfamiliar organizational landscapes, and during such transitions, communication may not have been operating optimally.

One indicator that may point to the presence of this challenge is the initial attempt by the German government to delay more overt actions by NATO prior to the outbreak of conflict. This position eventually shifted to German support for the collective position led by the US, after what seemed to be halfhearted efforts at stalling escalation.

This possible lapse in communication could have incurred numerous problems, not least of which is limiting the range of options presented to decision makers. Reduced intraorganizational communication affects even the most effective of institutions; it does not matter how many experts you have if those experts are unable to present their expertise to leadership.

5. Lack of Reassessment and Echo Chambers

The persistence of Germany’s position, even as the opportunity costs become more apparent over time, suggests a lack of "black box thinking"—the willingness to admit mistakes and course correct- by the German foreign policy apparatus. This indicates that not only could the current course persist, but that it may recur in the future.

This also points to the possible emergence of an echo chamber within German institutions, where certain perspectives may have been amplified while dissenting opinions suppressed, further limiting effective decision making.

Conclusion

With a large number of variables in play on the institutional and individual levels, even well established and well resourced organizations can be vulnerable to missteps. I deliberately chose Germany as a case study to emphasize that even resilient and strong institutions are vulnerable to the potential pitfalls described above.

All too frequently, evaluations of organizational decisions including those at strategic levels, attribute errors in judgement, analysis, or decision making to issues such as under funding, poor staffing, poor capacity building, or point to institutionalized cronyism or corruption. Alternatively, problems are often attributed to low levels of institutional memory or inefficient organizational hierarchies, none of which are present in the case of Germany.

Furthermore, by understanding that simply throwing resources at a problem does not guarantee successfully navigate a dynamically shifting landscape, institutions operating in the realm of international relations can focus their efforts on developing institutional agility and the necessary channels of communication to mitigate the risks arising from becoming overly rigid on the organizational level. We also infer the necessity of reducing the prevalence of echo chambers within organizations; complacency and dismissing opposing and dissenting voices can result in missing important opportunities.

In studying the contrasting roles of individuals versus institutions in shaping strategic positions, governments should consider the influence of individual actors within their organizations (ministers/officials/parliamentarians/etc.) on shaping decisions. They should further study the institutional safeguards in place to ensure that an individual point of view does not inflict damage on an organization’s medium and long term goals, while maintaining open channels for voicing alternative perspectives.

A key takeaway from this case study is that no government or organization is immune to errors in strategic decision making if they are ill prepared to face it; if it can happen to the German government, with the resources it has at its disposal, its precedents of successful foreign policy, and solid institutions, then it can happen to any government. Germany’s less than optimal foreign policy decisions amidst the Russo-Ukrainian conflict underscore the challenges even established institutions face in maintaining strategic agility.

To further explore this case, I conducted a thought experiment considering the question "what if Germany had prevented the Russia-Ukraine war?" where I looked at an alternate reality where Germany took a different set of decisions in the lead up to this conflict.