Rewriting Extremism: What Al Jolani’s Rise Means for the Region

Share

A new Syria has emerged. Ahmed Al Sharaa—once a wanted extremist—is consolidating power while the international community scrambles to reframe the narrative, in a way that may backfire spectacularly as we will explore together throughout the piece.

Türkiye, seen as the key player in the mobilization of the Syrian rebels in the overthrow of Al Assad, has reopened its embassy in Syria, and Qatar is set to do so on the 17th of this month. The U.S. and others have opened direct channels of communication with Al Sharra government. The Arab Contact Group -established to engage on the Syrian situation- held a meeting in Jordan with the participation of the France, Türkiye, Germany, the EU, the UK, the UN and the U.S. on the future of Syria.

Al Sharaa has held meetings with various international officials and representatives, chief among them the UN Special Envoy for Syria who urged an inclusive and credible transition into a new government. Al Sharaa has also stated that he has not made any decisions regarding the Russian military presence in Syria, in a step designed to assure Russia that their interests will remain untouched for the moment.

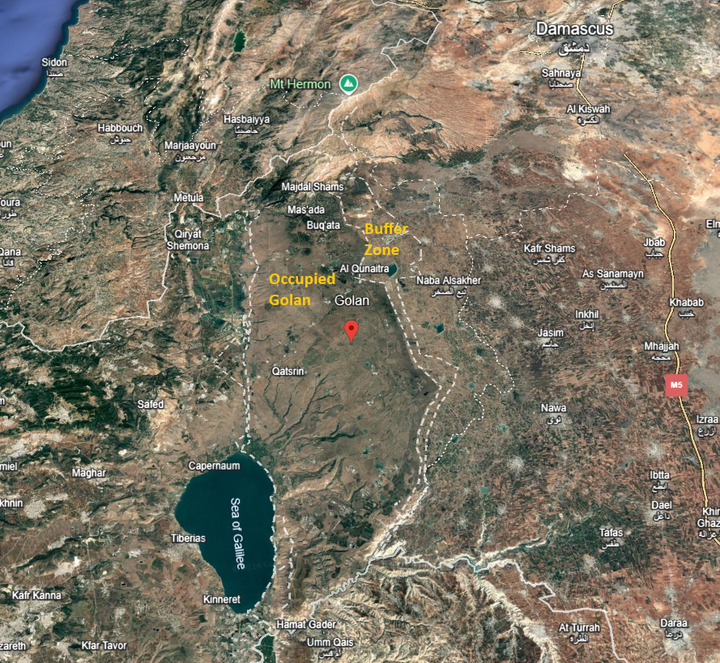

In the background, Israel continues to bomb Syrian territory and expand its occupation of the Golan, with Netanyahu moving to increase settlement activity in the occupied Syrian territory to appease his far-right expansionist government’s aspirations.

This flurry of activity signals multiple developments on the regional and international levels, with various actors vying to secure their interests and retain control over the coming period.

In their eagerness to engage and ensure their stakes in Syria, with their eyes glimmering with the potential political and economic gains to be made, it appears that the international community has either deliberately or inadvertently overlooked a few critical long term effects of their short term decisions.

Let’s go through the events and dissect why the decisions made today may not end up where actors think they will.

From Stalemate to Damascus in Days: How HTS Seized Syria

To understand the decisions of the actors, it may be useful to first get a quick refresher of the chain of events so far. While I covered this in more detail here , a quick briefing will help contextualize what comes next.

In late November, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), led by Ahmed Al Sharaa, launched a lightning offensive from northwest Syria against Assad’s forces . The Syrian army collapsed with minimal resistance, allowing HTS and its allies to sweep across towns and cities at unprecedented speed. By December 8th, they entered Damascus, and Bashar al-Assad was already half way to Moscow.

Al Sharaa, upon taking effective control of Syria, stated that there would be no dismantling of government institutions, leaving officials in their places and emphasizing that he sought a smooth transition into the new Syria. He instructed his forces and their allies to refrain from any revenge killings and prevent sectarian violence. HTS and their allies focused on freeing the thousands of political prisoners from Assad’s prisons and dungeons, rallying support for their role as liberators.

As events unfolded, Türkiye emerged as one of the key players on the scene. Effectively greenlighting the operation, the Turkish government stood out as the prime beneficiary from the fall of Assad’s regime: they now have a group in power in Syria that is not adversarial to Türkiye’s interests, stands ready to cooperate with Turkish interests and is unbacked by other foreign powers.

Russia granted Al Assad and his family asylum on ‘humanitarian grounds,’ while securing their interests in Syria for the interim period through discussions with the HTS; their bases remain untouched and their status unchanged.

The U.S. was quick to welcome the fall of Assad’s government, and in a mimicry of office politics, tried to claim credit for the fall of Assad by stating that it was the joint U.S. Israeli weakening of Iran and Russia that had led to Assad’s downfall. The EU welcomed the changes, and several countries quickly shifted their policies to stop processing asylum requests from Syrians.

Israel seized the opportunity to change the realities on the ground, with Netanyahu claiming that the Golan will remain under Israeli control in perpetuity, and the IDF running a protracted bombardment campaign in Syrian territory to declaw the remnants of Assad’s army. Israel also declared the 1974 Disengagement Agreement void and its forces entered into Syria (for more details on this see here ), and Netanyahu renewed settlement expansions on Syrian territory.

Talking Points and Contradictions: The Contact Group’s Dilemma

The Arab Ministerial Contact Group is a group of Arab ministers of Foreign Affairs established by the Arab League in May 2023 to seek a comprehensive solution to the Syrian crisis. Its members include Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and the Secretary General of the Arab League. It was formed on the occasion of readmitting Syria into the Arab League in 2023 to reopen channels of communication to find a resolution to the civil war.

On December 14–15, the group held a joint meeting with the U.S., UK, Türkiye, Germany, Qatar, the EU, France, Bahrain, and the UN Envoy to discuss the future of Syria. They issued a joint statement where they expressed their commitment to a Syrian led transitional period and the implementation of UN Security Council resolution 2254 . The statement also supported Syria’s territorial integrity and preservation of state institutions and access for humanitarian aid.

It also emphasized the necessity of combating extremism and terrorism and preventing the reemergence of terrorist groups, demanding that Syria not shelter terrorist groups or pose a threat to any country. These last few points of course are where things get interesting, because they are at the crux of the events that are unfolding before us at the moment.

These contradictions reflect the balancing act international actors are now performing—acknowledging ground realities while clinging to the rhetoric of anti-extremism.

Labels and Legitimacy: The Hypocrisy of Realpolitik?

While the bulk of the joint statement and the statements made by officials across the world on Syria predictably revolve around maintaining sovereignty and territorial integrity and stability, the references to the necessity of cessation of hostilities in Syria, the combating of extremism and terrorism, and preventing the reemergence of terrorist groups in the country stand out for their dissonance, as does the requirement that Syria poses no threat to any country.

The irony is hard to miss: a government led by a former ISIS and Al-Qaeda operative is now being asked to distance itself from extremism. The international community’s lip service to anti-terror norms starkly contrasts with its pragmatic embrace of Al Sharaa as Syria’s de facto leader. The implied possibility of reviewing the status of Al Sharaa as a wanted international terrorist, rather than exhibit political pragmatism, signals instead an effective delegitimization of the label.

If an internationally wanted terrorist can so quickly rebrand himself and his organization into a government with little to no backlash from the international community rather than be ostracized, it sends a set of very significant messages for others harboring similar ambitions in the Middle East and elsewhere. To get a clearer picture of how significant these decisions are, lets take a look at Al Sharaa’s considerable resume.

Ahmed Al Sharra, aka Abu Mohammed Al Jolani, had his first foray in combat in 2003 with his involvement with the Iraqi insurgency against U.S. forces in Iraq when he joined Al Qaeda in Iraq. He was captured in 2006 by the Americans and eventually released in 2011 as the Syrian Civil War was starting. He quickly returned to Syria upon his release and in 2012 was tasked by the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) (the precursor to ISIS) that was still affiliated with Al Qaeda at the time, to establish a Syrian branch of the group. He founded Jabhat Al Nusra in Syria on behalf of ISI (and therefore on behalf of Al Qaeda) to fight against al Assads regime.

In 2013, when ISIS (the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) separated from Al Qaeda and tried to absorb Jabhat Al Nusra, Al Jolani refused and remained allied with Al Qaeda instead, sparking conflict between Jabhat al Nusra and ISIS.

In 2016, Al Sharaa separated from Al Qaeda and rebranded his organization into Jabhet Fath at Sham to focus more specifically on Syria and quickly gathered allies and factions into a consolidated group that was renamed into Hayat Tahrir Al Sham, the group that led the assault on Assad’s forces and ultimately gained control of Syria.

From Al Qaeda, to ISIS, to the architect of a rebranded militant group now leading Syria, Al Jolani’s resume is rife with terrorist activity. His affiliation to extremist Salafi political Islam remains unchanged, although he has stated that his version encompasses a more inclusive and tolerant version of political Islam that will account for the diversity of Syria.

This shift in perspective, and his decision to pay lip service to all the right topics – By promising inclusivity, nonsectarian governance, and avoidance of conflict with Israel, Al Sharaa positioned himself as an attractive partner for global powers eager for stability.

Arguably, the fact that he and his group were responsible for the murder of civilians does not immediately disqualify him from contention to lead Syria as far as international actors are concerned, after all the current greatest transgressor against civilians par excellence in the Middle East remains the current Israeli government that the G7 have no problem in engaging with and even providing support in the form of weapons and political cover.

Their main consideration is the alignment of interests. With his statements and positions, Al Sharaa made it clear that he intends to pose no threat to Europe or the U.S. and that his focus remains Syria. He also presented a very welcome message to the U.S. and the Europeans through his nonalignment with Iran or Russia, effectively removing Syria from the chessboard of Iranian pieces to be wielded against U.S. interests in the regions (specifically Israel). He emphasized that he seeks to rebuild a new and free Syria.

This is realpolitik in its rawest form: interests reign supreme, overshadowing all else. But in their rush to secure short-term gains, international actors risk planting the seeds of future instability. This rapid change of posture toward a wanted terrorist (he remains wanted still per the U.S.), leading a group designated as a terrorist entity by the UN , without even undergoing the formality of delisting them from these designations could well lead to trouble down the line.

This rebranding not only legitimizes Al Sharaa but provides a dangerous template for others: extremism, if carefully repackaged, can earn global acceptance.

A Blueprint for Extremists

When a UN envoy shakes hands with the leader of a designated terrorist group—and global powers follow suit with conciliatory tones—the message doesn’t just resonate locally. It creates a blueprint: extremism can be legitimized if it achieves power.

For states and governments, it is a calculated political necessity of dealing with the realities as they stand rather than how they ‘should’ be. It is a fairly predictable bureaucratic response pattern that recurs with fair frequency: you deal with the person in charge and with whom you may be able to reach mutually beneficial agreements and turn a blind eye to anything extraneous (for examples you can explore almost any movement that gained power through armed conflict across the past century).

For intergovernmental organizations, particularly the UN, engagement doesn’t equal legitimization, it merely acknowledges control. The UN needs to engage with whoever can allow them to deliver humanitarian and other assistance to those in need. That being said, the manner in which the organization chooses to engage makes all the difference: tone matters.

The UN Envoy Geir Pedersen, in the press conference after meeting Al Sharaa, referred to the victorious coalition as the ‘caretaker government’ and added that there is united international community ready to support Syria. The implied message to Al Sharaa is clear: say the right words, strike the right pose, and even Security Council resolutions can be sidelined. For extremists, this is a playbook waiting to be replicated.

We can dismiss the sanctions imposed by the U.S. and the EU, which are simply the tools they wield against whatever state or entity that they disagree with politically; there’s no real objective measure, so they will either stay in place or be removed whenever the actors deem it suitable to their interests to do so. The U.S. designation of Al Sharaa as a terrorist hinges largely on his political convenience to American interests, although it will be interesting to see how the incoming administration approaches this particular issue.

What all this adds up to however is a collective of messages that is making its way through the political ecosystem in the Middle East and globally: just because you’re a violent extremist organization does not mean that you will remain ostracized in perpetuity because all you have to do to attain rebranding is win actual control over a territory and then ensure you align yourself with the interests with key global and regional powers and you will be all set.

This should ring alarm bells across the Middle East where political Islamic movements have largely been pushed underground but remain at the forefront of collective consciousness. Factions harboring militant Islamic ideology now have a roadmap to political legitimacy. They also have a powerful set of arguments to wield against current Arab governments; they can capitalize on the inability of any Arab government to intervene or curtail Israel’s attacks across the region. They did not succeed in any of their efforts in restraining Israel’s carnage in Gaza, nor did they succeed in impeding its bombardment of Lebanon, nor could they slow down its growing warpath in Syria. They stood by as Iranian missiles flew toward Israel over their airspace, and appeared to have little impact on the political narrative of the region as it is shaped now by global and regional actors; Iran to the east, Türkiye to the north, while the U.S. and Russia bicker over control of the region.

Emboldened by this potential path to legitimacy, it is expected that Islamist groups will adapt in their outreach and recruitment processes throughout the region. They can at one at the same time decry the weaknesses of current governments, promising salvation from the oppressive foreign interventionists, while at the same time catering to the interests of those same alleged enemies. They can execute acts of violence across the region, while accusing national governments of colluding against their people, at the same time inflicting grave harm on those same populations.

With all these elements in play, if Al Jolani and his group are allowed to govern Syria, we can expect some copycats to emerge in the not too distant future.

A Region on Edge: Fertile Soil for Extremist Ambitions

The Middle East is primed for extremist recruitment. The devastation of Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria—paired with rising uncertainty across the region—has created a perfect storm of fear and frustration.

Extremist groups sell fantasies of a time of glory, of unity and empowerment that somehow they, unlike any other actor in the region, will deliver. Like other far right groups and political actors, their main selling point is a combination of fear and hope. The fear that anyone can be next to face destruction like Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq before them. They then present themselves as the saviors: they’re the only ones who will be able to protect the people from these foreign invaders.

It is of course unclear and vague how they would achieve this once they obtain power. Every iteration of political Islam that has come to power so far immediately worked to isolate its internal opposition, while focusing on consolidating control and either implementing anachronistic and rather archaic versions of Islamic law or simply becoming an Islamized version of other governments in the region.

On the one end of the spectrum, you have the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt that immediately adopted the same basic behavioral patterns of its predecessor government but with some Islamic flavor and was very quickly ousted from power, and on the other end you had ISIS in Iraq and other places burning people alive and doing their best to mimic the landscape of Mad Max movies.

Regardless of the endgame, or the where the groups lie on the political spectrum, they will see in Al Jolani’s rebranding into “Mr. Al Sharaa the head of the Caretaker Government” in Syria an opportunity for their own aspirations: maybe they could also achieve a similar target through careful calibration of approaches: balance ideology with pragmatism, secure territory, and rebrand into legitimacy. The lesson is clear: power may not erase the past – but it can rebrand it.

This opportunity, coupled with the increasing frustration with the helplessness of Arab governments, will probably result in an uptick in recruitment efforts across the region using everything from social media to games to apps, and other means.

By legitimizing Al Jolani, the international community has set a dangerous precedent. Extremist organizations now see a clear roadmap: seize control, align with power, and the world will turn a blind eye. The short-term gains may come at a steep long-term cost—one the region can ill afford.

When Power Erases Extremism

The rise of Ahmed Al Sharaa is more than just a shift in Syria—it’s a dangerous precedent. If they turn a blind eye to his extremist past and embrace his rebranded leadership, international actors could sent a clear message: power erases history, and pragmatism outweighs principle.

For extremist groups across the Middle East, this moment could prove a revelation. It shows that with calculated strategy, territorial control, and the right alliances, legitimacy can be achieved. The blueprint is now public, and the seeds of its replication are already sown.

The short-term gains celebrated today—stability, cooperation, and alignment of interests—may come at a cost no one can afford tomorrow. If extremism can be legitimized once, it can happen again.