On Becoming a Diplomat

Share

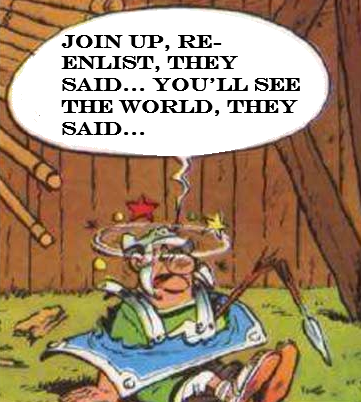

Stepping into a career of diplomacy is a big decision, one that affects not only your professional path but every aspect of your life. It is a world unto itself, interspersed with opportunities unlike any other. You will have the chance to travel, work, and live in places that you would otherwise have never thought of. Not only will you rub shoulders with some of the world's most powerful figures, but your work, your decisions, and your input will also influence their decisions and potentially shape global narratives.

Yet, choosing this path is far from easy. Diplomacy demands the agility to uproot your life every few years and the fortitude to perform under unfamiliar and sometimes unfriendly circumstances. You will be expected to look like you belong everywhere you go, while never quite feeling like you fit in.

The invisible skill set essential for diplomatic success comprises a mix of adaptability, resilience, and nuanced interpersonal skills—attributes that can define the trajectory of your career. The theoretical foundations including the hard skills in analysis, international affairs, and navigating bureaucracies, are important but relatively easy to acquire when compared to the elements we will explore below. Having the hard skills without the aptitudes leaves many in the field in a perpetual state of discomfort and frustration.

Remember, there are easier ways of avoiding parking tickets than becoming a diplomat.

Adaptability & Reinvention

Diplomatic life unfolds in a perpetual dance of beginnings and endings. Each new posting births a fresh chapter, demanding the reinvention of not just routines but the very fabric of one’s life. In what I describe as the “diplomatic lifecycle,” they experience a repeating virtual cycle of birth, growth, decline, and death over the course of their postings. With every new posting, a diplomat is uprooted and replanted into an entirely new setting, a new house, a new office, a new set of responsibilities and an entirely new set of routines. They have to work with a new set of colleagues, a new head of mission, make new friends, and create a new social network.

The reaction to this cycle is what differentiates one person from the next; there are tremendous variances between different people’s reactions to it. Where one person may welcome the challenge, finding it invigorating and refreshing, others may find it to be exhausting and draining. Its effects inevitably reverberate throughout the duration of a diplomat’s posting, and as a consequence has a cumulative effect on their state of mind over the course of their career.

This is where the trait of adaptability comes in; because the overhaul extends to every facet of their lives, and because it is a frequent and recurring occurrence, having or acquiring this trait is integral to the successful pursuit of the career. It provides the foundation upon which everything else is built. For a diplomat, adaptability entails the ability to reinvent every aspect of their lives to align with their new setting. They are not only expected to survive in a new context, but to thrive and deliver on all fronts.

The ability to adapt to new circumstances will dictate the course of a diplomat’s career. Even if they are the foremost analyst on international affairs, with a mastery of research and data collection, and the ability to write reports in their sleep, it will not matter much if they are unable to wield those skills as because of the mental strain of adapting to a new situation.

The difference between having this trait and not is the difference between experiencing a journey of discovery and being dragged kicking and screaming from one place to the next. If you dread recurring change rather than welcome it, every step of the way will be significantly more difficult for you.

Resilience and Recovery

Change is the heartbeat of diplomacy. Each posting is a roll of the dice, where diplomats might face a tapestry of challenges, from harsh environments to demanding workloads. Resilience, thus, becomes their shield, and recovery their strategy for long term success. Postings can be in hardship stations, missions with toxic work environments, or in understaffed and severely overworked stations. They can be in places where there is a significant drop off in the quality of life, or places with widespread security or health issues. If you are particularly unlucky, you could end up with the whole collection in a singular posting. A diplomat has to be resilient, not only on the professional front, but also on the personal one.

Resilience and the ability to recover from difficult situations is a critically important element in the personal attributes required for this career. In diplomacy, there are often concurrent periods of perpetual low-level stress peppered with periods of high-level stress (read through Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers for more on different kinds of stress). The ability to navigate both of those in parallel will delineate the difference between sailing the waters of global affairs and the perpetual feeling of floundering that permeates the field. [1]

Gritting your teeth through a challenging posting is one thing, but letting a negative experience color your expectations for the entire career creates long term problems for any diplomatic career.

Connecting With People

The moment a diplomat sets foot in a new posting, the clock starts ticking. Building a robust network isn’t just a task—it’s a lifeline. Effective diplomacy thrives on the depth and breadth of connections. Socializing and networking are therefore an integral part of the package, which means you have to actively work on your people skills if you pursue this career.

The expectations on diplomats are not just to meet in boardrooms and meeting halls, but also to interact across the social spectrum of your host country. You are expected to build relations across the community, be present at events, and engage proactively with as broad a spectrum of people as possible. Introverts may find this issue more challenging, but it is not an insurmountable hurdle.

One of the most important resources at a diplomat’s disposal therefore is the ability to connect with people. The difference between a diplomat and someone doing secondary research is the depth and nuance that develops from contextual presence, the perspective offered by a consistent stream of interactions on the ground, and the direct channels of communication offered by a strong network of connections.

The versatility needed under the umbrella of this skill is as important as the skill itself. A diplomat must be able to engage with high-ranking powerful people without being intimidated and must be able to connect with people with different backgrounds, interests, and cultures. If this comes naturally to you, you already have a distinct advantage, and if it does not, it is a skill you should seek to develop early in the pursuit of this career.

Set Your Expectations

Understanding the true nature of diplomacy is vital to avoid disillusionment. I have seen diplomats from different backgrounds who entered the field envisioning themselves as ambassadors of their people or upholders of a set of values and principles only to discover that in reality they are emissaries of their respective governments. It is an important but often overlooked distinction that needs to be taken into consideration prior to seeking to join the career.

As a diplomat you are employee of the executive branch of your government. You receive your instructions from the ministry of foreign affairs (or equivalent), which itself receives guidance from the political leadership of the government. Diplomats are neither elected officials representing the people of their countries, nor are they promoters of any specific set of values. They represent, in all their interactions and regardless of personal beliefs, the positions of their government.

It is important to emphasize this point because of the cognitive dissonance permeating diplomatic circles among those who entered the career without that distinction in mind. The dissonance resulting from the clash between the self-perception of representing a set of values or positions and the reality of representing a government can be mentally draining. This is particularly true for diplomats who hold values that diverge significantly from official positions of their government (which is not uncommon).

Is it Worth It?

If you take on board the elements discussed above, and you find them manageable rather than intimidating, then you might just find that despite all its drawbacks it is an extraordinary experience on both the personal and professional levels. You will have access to people, places and experiences that you would not have thought possible. You will learn how the world works, what drives it, you will find commonalities between people from opposite sides of the globe. It will dissolve many of your preconceived notions about the world, and grant you perspectives and outlooks that may not otherwise have been attainable.

If you're ready to walk a tightrope of bureaucracy and excitement, uproot and start over every few years, let go of the familiar and welcome the unfamiliar, and to accept that you may be a perpetual foreigner—even in your own country—then diplomacy might just be the adventure you're seeking.

[1] An interesting evolution of the concept of resilience is covered in the book ‘Antifragile’ by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, where he posits the notion of not only navigating stress, but welcoming and thriving in difficult situations.