Netanyahu’s Golan Gamble: Calculated Provocation or Strategic Choice?

Share

Benjamin Netanyhau opened up yet another front in Syria, fueling the cycle of conflict in an attempt to perpetuate the wars in the region to hold onto his power and maintain relevance by catering to the territorial aspirations of the Israeli extreme right that is using the conflict to mobilize support for its greater Israel project.

In the wake of the collapse of Bashar El Assad’s regime on 8 December, Israel declared the disengagement agreement of 1974 void and launched an incursion into Syrian territory. The Israeli army launched attacks on numerous targets within Syria, destroying much of the naval fleet, and other military and security targets within the country. Netanyahu then stated that the Golan heights will always be a part of Israel, laying claim to the Syrian occupied territory. This was not the first time Netanyahu made this statement, having done so previously in April 2016 and again in 2018 .

Strategic Heights: A Brief History of the Golan

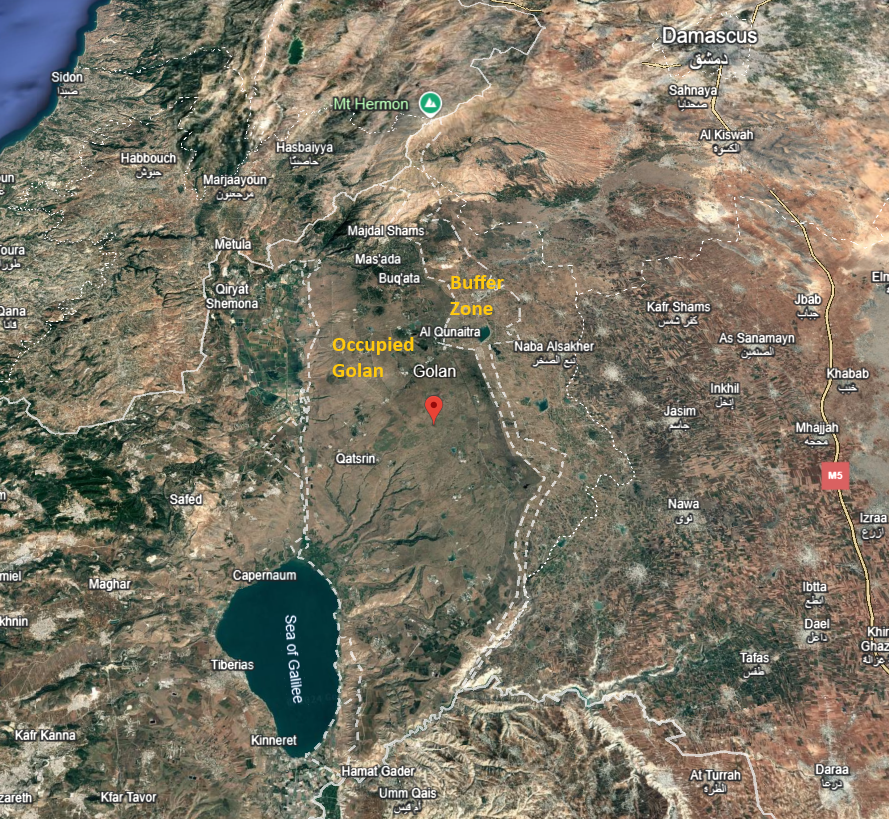

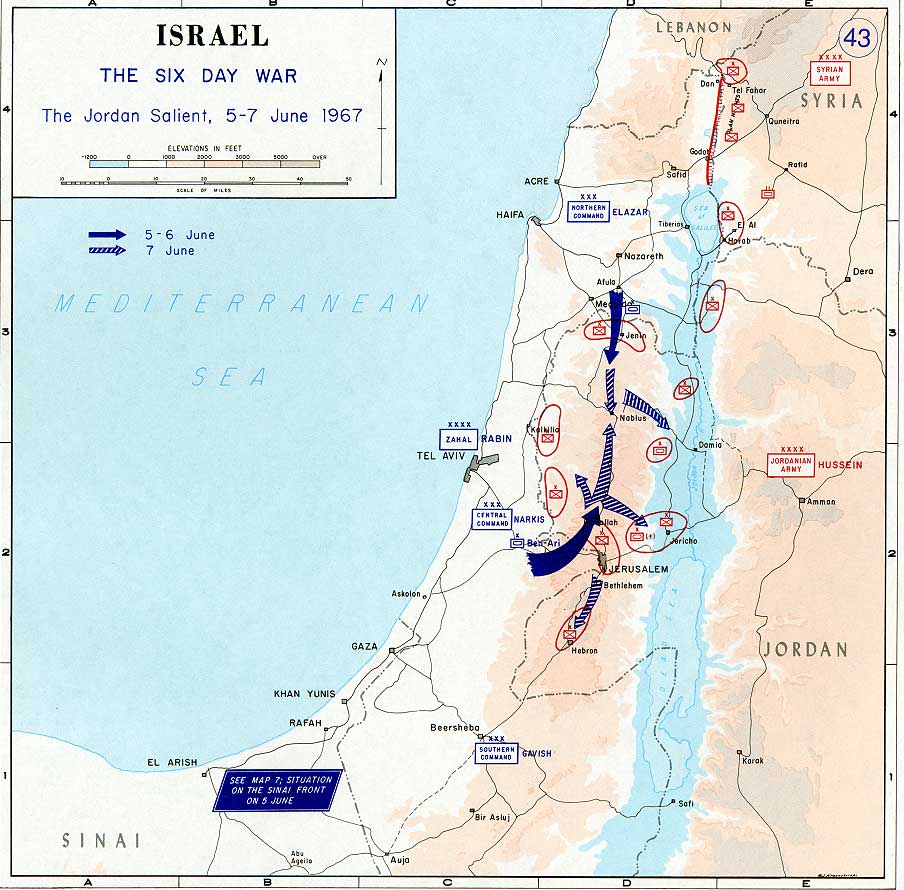

The Golan heights are an elevated plateau overlooking the Jordan Valley which is home to Lake Tiberias (aka Sea of Galilee) and the Jordan river. Israel captured the Golan in 1967 during the Six Day war, and by capturing it, achieved military dominance over the surrounding terrain and an ability to early detect any threats it perceived, launch attacks with impunity if it so chose, and maintain strategic military superiority.

In 1973, Syria launched an offensive in an attempt to regain the territory, timed in conjunction with the Egyptian operation to reclaim the occupied Sinai Peninsula. While the Egyptian operation was ultimately successful, resulting in the peace treaty between Egypt and Isreal, Syria failed to recapture the Golan, and ultimately was compelled to sign the Disengagement Agreement with Israel, which stipulated that there would be a buffer zone, a separation of forces, and an observation of ceasefire on land, sea and air. This left the occupied territory under Israeli control, but limited Israel’s expansion into Syrian territory, with the UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNODF) established to ensure compliance by the actors.

In 1981, Israel legislated the “Golan Heights Law”, extending Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to the territory effectively annexing the territory (although the law itself stopped short of using that term). It reasserted its claims to the region through rapidly engaging in settlement construction in the area to consolidate its presence and make any negotiations on Israeli withdrawal from the area impractical.

In addition to the military advantages that the Golan Heights offer, it has the added dimension of being one of the sources of fresh water for Israel. The rainwater catchment area in the Heights feeds into the Jordan river, which is one of the sources of fresh water for Israel, making the heights not only a matter of military concern, but also one of water security.

Israel’s occupation of the territory is illegal under international law, and its effective annexation of the Heights was rebuked by the UNSC in its unanimous resolution 497 in 1981. The resolution declared the Israeli annexation and imposition of law on the Golan to be “null and void” and a violation of international law. The U.S. recognized Israel’s claim to the Golan in 2019 under President Trump, but no other country recognizes Israel’s claim to the territory.

Short-Term Gains, Long-Term Risks

Assad’s fall signaled an important shift in the geostrategic situation; a window opened for Israel to critically reduce the military capabilities of Syria. In the chaos ensuing the fall of Assad and the rise of the rebel forces to power as they attempt to gain control of the country, there was no clear international backer for the new Syrian de facto authorities, allowing Israel to act with relative impunity against targets within Syria. Israel's actions in Syria before Assad’s fall were tempered not by the Syrian military itself but by the robust backing of Assad's regime from both Russia and Iran, which had acted as significant deterrents.

The collapse of Assad’s government signaled that neither of those actors would be likely to rise to the defense of Syria at this moment; the power vacuum provides Israel with an opportunity to inflict extensive damage to Syria’s military capabilities without fear of reprisals. It also presented Israel with an opportunity to consolidate its control over the Golan heights, positioning itself strategically to launch offensives against any government that forms in Syria that it considers a threat. On the short run, the dismantling of Syria’s military capacities weakens the security architecture of the new Syrian government, whatever form it takes, and ensures Israeli military superiority over Syria. This temporary advantage, however, risks creating a vacuum that other actors, such as Türkiye, could exploit to assert their influence.

The decision to mobilize its forces reflects various considerations, largely political, that improve Israel’s position in the short term. By opening up this front in Syria and making several gains in the interim, it provides itself with more leverage in any upcoming negotiation.

If it gets away with its short term gains, the right wing government achieves multiple goals, first and foremost gaining more territory, galvanizing further support from its base to remain in power and pursue its expansionist policies in Syria, Palestine and elsewhere. It can also leverage this new front in Syria to acquire further military support from the U.S. under the guise of countering further security threats arising from the new militant government in Syria (which suits the U.S. just fine).

It also improves its position in any foreseen negotiations in the upcoming period. These short-term gains provide Israel with bargaining leverage, allowing it to dictate terms in future negotiations while avoiding substantial concessions. Rather than making real concessions, it has positioned itself to ‘concede’ any new gains it made in this interim period without having to give anything else up, whether in negotiations with Syria or on the Palestinian front.

The Politics of Provocation

Despite the apparent gains made by Israel by employing this aggressive posture, there are questions about the real long term gains made; the gains serve the purposes of the Israeli right wing, but they may be of limited real value to other political factions within the country.

Netanyahu’s renewed claim regarding the Golan Heights appears calculated to elicit antagonistic responses reinforcing his domestic support base while framing regional actors as threats to Israeli security. The claim adds nothing of value to the situation on the ground where Israel is already in effective control, but by portraying other actors as threats, he can leverage their actions to perpetuate the conflict for as long as possible to keep the reigns of power and ward off his opponents within Israel.

Ahmed El Sharaa’s nom de guerre is Al Jolani, meaning the one from Golan. His credibility moving forward will rely on several factors, chief among them Syrian independence from foreign influence, and the creation of a strong Syria poised to reclaim its position in the Middle East. By making this claim at this stage, Netanyahu directly and deliberately impugns Sharaa’s credibility among his support base: how can you claim to be a liberator if you don’t oppose the country occupying your land? At this stage however it appears that El Sharaa has not taken the bait, focusing on establishing a semblance of order through Syria’s territory before venturing into confrontation externally.

The hundreds of strikes executed by the Israeli military effectively decimated the already weakened Syrian army. The Syrian army itself posed limited threat to Israel; since 1967 it has been unable to make any headway or compete or even effectively defend itself against Israeli aerial incursions. It is an army that fell to a rebel force with limited equipment and presented little opposition to the incoming forces, falling in less than two weeks after years of stagnation.

El Sharaa and his group effectively inherited a crumbling military, with outdated weapons, reliant on external forces for support and defense, and would have been burdened with how to deal with this collection of junk. By eliminating that arsenal, Israel effectively handed El Sharaa (or whoever ends up at the head of Syria) an opportunity to call on potential suppliers and allies to completely renew Syria’s military architecture without the need to figure out a way to get rid of older equipment. It also provided him with extensive justifications for the need to purchase weapons, particularly defense systems, to ensure security: he can simply point to Israel’s actions and leverage them to purchase an upgraded set of weapons to ensure Syria’s defense and independence. Turkey, China and possibly even Russia, may be poised to provide such support, with Turkey in particular intent on ensuring that Israel does not maintain an unchallenged sphere of influence in post Assad Syria.

The extreme right wing in Israel remains at the helm of Israel’s government, wielding its ability to collapse Netanyahu’s government to ensure his allegiance to their policies; their ability to expose him to the judicial system through withdrawing support ensures his adherence to their expansionist vision, and at the same time he is using their power base to galvanize support for a protracted and perpetual state of conflict that shields him from the array of legal concerns that he faces. This faction of the government seeks to establish control over broader swaths of territory over what they describe as “greater Israel”, and Netanyahu is happy to go along with this approach insofar as it serves his interests.

From Power Vacuum to Power Plays

This short-term strategy could hold if the U.S. and its allies (primarily the G7) swoop in quickly enough to provide the incoming Syrian government with enough incentives and assurances to hold their ambitions at bay. If, in the aftermath of this Israeli decimation of Syria’s military infrastructure, the U.S. and the G7 position themselves as guarantors of Syria’s integrity and security, they could motivate the rebel factions to relinquish military aspirations and focus on rebuilding the country, give up aspirations for the return of the Golan, and effectively remain demilitarized.

However, given the plummeting credibility of the U.S. as a broker of peace in the Middle East, this may be unlikely in the long term; while the rebel factions with El Sharaa at the helm may see opportunities in the short term to acquiesce to some suggestions, they are unlikely to maintain that position once they have consolidated power. It is more likely that they will seek out a balance of alliances between different global and regional powers, leaning on one (like China for example) for infrastructure and reconstruction, on another (Turkey for instance) for rebuilding its defense capabilities, a third (the U.S.) to provide some security coverage against Iranian encroachment, and another (say Russia) as a short term security umbrella against Israel.

If El Sharaa takes Netanyahu’s bait and adopts an adversarial stance against Israel, Netanyahu can use it to justify further Israeli aggression against a weakened and disarmed Syria. This may incentivize Sharaa to play the waiting game and regroup, reorganize and reposition before effectively taking a stand. However, if he adopts the quiet approach, his credibility as a liberator may be actively undermined by some of the factions within the coalition that defeated Assad’s forces. On the ideological front, his position as an Islamist leader may also be questioned by members of his coalition if he fails to take a position against Israel’s incursions in Syria.

Syria’s new government is taking shape, with El Sharaa appointing cabinet positions and suspending the constitution and parliament for three months, and actors regional and international are vying for credit for the downfall of Assad’s regime, alluding to the weakening of Assad’s support network in Russia and Iran. These claims lay the groundwork for their involvement in the post Bashar Syria, which for the U.S. includes ensuring Israel’s military superiority. (for more on the aftermath of Assad’s fall see here).

Given the role of Türkiye in the downfall of Assad, and the likelihood that an arrangement was reached between the rebels, various international actors (possibly including Russia), and Assad to allow his departure in exchange for not protracting the conflict, Türkiye may have greater influence than any other actor in insofar as the next steps within Syria. The U.S. scrambled to respond to the developments, while Türkiye appeared to be well informed beforehand.

If in fact Türkiye becomes the key partner, then the alliance with Syria will be built on multiple points of mutual interest, including the necessity of balancing Israel’s growing military hegemony over the region, securing the flow of gulf gas through Syria north to Türkiye, and securing their border. Unlike the U.S. Türkiye could take over from Iran and bolster Syria’s strength in the short to medium term to contain Israel’s growing power in the region, and secure its own access while broadening its sphere of influence. However, Türkiye's involvement could come with its own complexities, as Ankara’s regional ambitions may not fully align with Syria's long-term interests.

Competing Interests, Divergent Paths

With Israel unlikely to change its course or policy in the short term; it is expected to try to maximize its advantage while it can and before the new government consolidates partnerships with any significant international backers capable of deterring further action. Once global and regional actors enter the scene, it will be more difficult for Israel to engage in the same level of attacks with impunity.

Israel's actions in Syria can also be viewed within the broader regional dynamics and the shifting balance of power. If Türkiye emerges as a guarantor of Syria's sovereignty and a counterweight to Israel's regional dominance, while reshaping alliances in the Middle East. This partnership between Ankara and Damascus, driven by shared security concerns and economic interests, has the potential to reshape the post-Assad regional order. For Israel, the consolidation of a Turkish-Syrian alliance could curtail its ability to act unilaterally, introducing a new layer of complexity to its military calculus in Syria.

The aftermath of Assad's fall and Israel's subsequent actions in Syria highlight the tenuous balance of power in the region. Netanyahu's aggressive posture may yield immediate political benefits, but it risks overextending Israel's strategic reach. A fragmented Syria, while weaker in the short term, could eventually evolve into a more robust actor through diversified alliances with global powers such as Türkiye, China, and Russia. The uncertainty surrounding Syria’s next moves incentivized Israel to seek maximum short term advantages, but there are further considerations that need to be considered.

While the Hayat Tahrir Al Sham and its leader Al Sharaa are designated as terrorists (which could change if they align their interests with the right actors), their policy of restraining their fighters from engaging in revenge killings and sectarian violence, and their decision to not dismantle the government structures but rather keep them in place to rebuild the country have garnered them extensive support and sympathy throughout Syria. Basking in the glow of the post victory euphoria, they have been promoting themselves as liberators of all Syrians rather than a specific sect.

This broad appeal and support base, if built upon and fostered would be disadvantageous to Israel; a weak and divided Syria is far more palatable than a strong and cohesive neighbor, and we may therefore see Israeli political maneuvering with the U.S. and other western allies to promote a form of government in Syria that entrenches divisions rather than unity in Syria. These could take the form of governments that allocate specific percentages to sects or factions within the government, ensuring a perpetual state of mistrust and internal dissent that makes it difficult to counter external pressures, threats or attacks.

The possibilities are vast, but the eventual trajectory will hinge on key decisions by regional and global actors in the coming weeks, as they grapple with competing interests and shifting alliances: will the U.S., in an attempt to rebuild some credibility in the region, reign in Israel’s offensive? Will Türkiye take a stand? Will Russia or Iran seek to reestablish their roles? Will Al Sharaa manage to rebrand his image and retain control? Will the rebel factions fall to infighting and division? Will the U.S. and Türkiye reach an arrangement regarding Syria that balances the interests of both actors vis-à-vis Syria and Israel?

The outcomes will depend on whether regional and global actors prioritize stability and cooperation or determine that cycles of competition and conflict suit their interests better.