Machina Ex Diplomacy

Share

This will be the first in a series exploring AI-related issues in diplomacy and international affairs. Initially, I planned to cover this topic in one piece, but due to the rapid development of the field and the complexity of the issues, I decided to break it down into a series that will unfold as developments emerge. This piece will serve as a starting point, taking an overview of the overarching themes currently permeating the role of Artificial Intelligence in the context of international relations. Following pieces will explore individual issues with more depth.

****

When the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopts resolutions on Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Secretary General of the UN establishes an Advisory Body on AI, it signals that AI has seeped into the collective consciousness of governments the world over.

Although many governments have started exploring the challenges and potentials of AI, these efforts have largely remained within the scope of national borders. The inclusion of AI in multilateral discussions underscores a growing recognition that AI transcends national boundaries. It also points to the fact that countries on the wrong side of the digital divide are beginning to realize the magnitude of impact that this technology presents.

AI’s impact on international relations will likely reverberate across the entire sector. While its potential uses in global diplomacy are vast and still largely uncharted, the ongoing efforts to explore these applications are now bearing some fruit.

By identifying where governments and intergovernmental institutions stand at this moment in time in their approach to AI, it will be easier to determine the potential trajectory of integrating the technology into their diplomatic and international relations practices.

I have scoured various strategies, laws, draft regulations, and other official documentation that codify the manner in which various governments across the world are dealing with the advent of AI. I have also looked at the resolutions adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, and the Report of the Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence established by the Secretary General of the United Nations.

Governmental Outlooks

One of the more common themes among governmental outlooks is deep concern. The realization that not only has this technology materialized, but that it is also being developed outside the scope of regulatory frameworks that governments have at their disposal, and that its development is largely being led by private sector entities driven by corporate rather than governmental or public priorities.

Reflecting this concern is a pervasive theme of regulation. Governments are exploring mechanisms to regulate and oversee the development of this technology, while striving to remain involved in the process and retain some measure of control over the trajectory of its progression, or at least remain aware of it.

National strategies also reflect a certain level of concern about the pervasiveness and potential ubiquity of the technology, raising issues of privacy, misuse, and the its potential deployment in violating citizens’ rights.

Conversely, several documents also reflect an intent to support AI development, enhance capacity building, and increase public involvement. There is also an undertone of seeking access to the technological references, even if not in outright terms, reflecting both the critical issue that governments are lagging behind the private sector in terms of development of AI, and at the same time the steps being taken to mitigate the lag.

Intergovernmental Outlooks

As national governments grapple with AI's implications, the role of international organizations becomes increasingly important. Member states of the UN, for instance, have begun addressing AI at the multilateral level, highlighting the need for global cooperation to regulate and harness the technology.

During the High Level Week of the UN General Assembly, held from the 23rd to the 27th of September 2024, two important meetings covered this topic, the first is the Summit of the Future, which within its adopted document -the Pact for the Future- reaffirmed the concerns included in the resolutions, as well as the outlooks of cooperation, and possible governance mechanisms.

The second was the High-level Meeting on International Cooperation on Capacity-building of Artificial Intelligence, cohosted by China and Zambia. The stated focus of this meeting was to explore ways to address the digital divide, enhance cooperation on AI and enhance access to the technology in order to spread its benefits on a global scale.

During the meeting, China announced its "AI Capacity-Building Action Plan for Good and for All," through which it states that its intention to promote connectivity, empower industry, and enhance literacy. It reaffirmed its commitment to engaging with other countries on all those fronts, and establish an international cooperation platform for AI capacity building. Additionally, it stated that it will hold capacity building programs and share resources and invest in the development of people and infrastructure.

Indicative of the framework within which AI is being explored in the intergovernmental context, the two resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly regarding AI, as well as other adopted documents, stress the need to contextualize AI within the existing frameworks of the United Nations Charter, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and established international principles. They in essence provide, according to the resolutions, the yardstick by which the compliance of AI activities and development can be measured. They also provide the foundation of principles upon which international regulatory frameworks pertaining to this technology will be based.

The issue of the digital divide is also a core focus point of engagement on the intergovernmental level. The Global South has recognized the risk of being left behind and is vocally engaging with partners to address this concern, a matter which China responded to quite effectively with its aforementioned Action Plan.

Addressing the digital divide is closely correlated to the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), in particular Goal 9 related to fostering innovation, developing resilient infrastructure, and increasing access to information technology. The resolutions also acknowledge the importance of keeping pace with the development of AI and call for increased international cooperation, including some mechanisms for technology transfers.

At this stage intergovernmental engagement is still tracing the outlines of how future cooperation on the issue will evolve. With a number of concerns already raised, and basic frameworks emerging, and various actors are positioning themselves in the field, patterns will begin to form with greater clarity.

UN Outlook

While the resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly reflect the positions of the member states, the Secretary General of the United Nations has spearheaded the organization’s efforts in contributing to the conversation. The UN Secretariat, made up of professionals from every member state working towards the implementation of the common goals of its members, is also exploring the technology. As the primary intergovernmental global body with agencies responsible for every facet of international cooperation from peacekeeping to international development, it seeks to use this technology to achieve the goals of the UN, and provide early warnings to governments on its potential challenges.

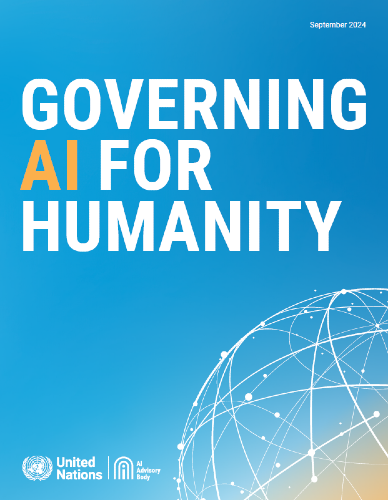

The Advisory Body on AI -established in October 2023- recently issued its report "Governing AI for Humanity" The report addressed in greater detail and technical specificity the concerns that governments have voiced on the national and international levels. It addresses the pressing need for governance mechanisms, enhancing global cooperation, intergovernmental and interorganizational efforts to coordinate global action on AI. It further discussed mechanisms and models through which these goals could be achieved.

The report also addressed the impact of AI on international security and the spreading use of the technology by militaries around the world through the use of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS), a matter of growing concern on the international level with both the Secretary General of the UN and the President of the International Committee of the Red Cross calling for treaty negotiations in their regard.

The Advisory Board issued a series of recommendations in the report to foster and formalize a coherent and cohesive effort on AI. The recommendations included establishing an independent international panel on AI, a twice yearly multi stakeholder policy dialogue on AI, creating an AI standards exchange to unify standards internationally, creating a capacity building network, establishing a global fund for AI, creating a global AI data framework, and establishing a permanent office for AI within the UN secretariat.

These recommendations revolve around the need to unify the direction of cooperation, develop guardrails and safeguards, and mitigate the risks of the technology while making optimal use of it. They also seek to reduce the risk of a growing digital divide, which would result in increased disparity in access to and benefits from the technology.

Mirroring the concerns of governments on the technology, the UN secretariat and its Advisory Body provided through this report a series of proposed actionable steps that may help stakeholders -governments, intergovernmental organizations, and non-governmental actors- agree on their next steps.

The International Relations AI Landscape

AI is inevitable and the tone within diplomatic and global circles reflects this sense of inevitability; AI is seen as an unstoppable technology that will -sooner rather than later- permeate the international relations system at every level.

Already, branches of governments have begun introducing AI into their systems, including armaments and other technical fields, and we can expect ministries of foreign affairs and other agencies dealing with international relations to follow suit. Already various ministries of foreign affairs around the world have begun introducing the use of AI for analyzing large amounts of data and speeding up processing of information. Others have introduced more creative uses like Ukraine's use of an AI spokesperson named Victoria.

AI is at the same time a source of worry and optimism in the collective consciousness of ministries of foreign affairs across the world. On the one hand, it could make their jobs easier, and on the other hand it could end the world.

The ambivalent messaging from national governments and intergovernmental organizations attempts to balance between optimism and caution. On the one hand there are numerous concerns about the technology itself, about its scope, its reach, the lack of transparency of its technology, and the lack of regulatory mechanisms. On the other hand, there is outlook towards the potentials that the technology offers, its uses for sifting through vast amounts of data, its pattern recognition capabilities, and its potentials as an early warning system, to name a few.

Mutual suspicion is the name of the game when it comes to international relations, and AI is no exception. Governments across the world, even as they seek regulatory mechanisms on the technology are concerned with how other actors may use the technology. Binding themselves to certain regulations while others act freely would inherently place them at a distinct disadvantage. Exacerbating the matter is the existing divide in access to technology, and the Global South is increasingly disconcerted that AI may exponentially widen the digital divide if they do not act rapidly to obtain the relevant knowhow and expertise.

In addition to the mutual suspicion between governments, there is a collective dread when it comes to the gap between public and private enterprise in the field of AI. As the main drivers of development of the technology, corporations that are driven by profit may not share the same perspective of governments seeking broader goals. Tying into the issue of governance, governments are delicately exploring how to govern private enterprise in this field while reaping the benefits of their findings.

The primacy of governance in the discussions about AI stems from the technology’s unprecedented applications, scope, and rate of development. The challenges inherent in drafting legislation and developing governing mechanisms -for technologies that are not yet fully understood- is causing considerable consternation among those responsible for these efforts. Whether we look at the report from the Advisory Body on AI, or we read through the resolutions adopted by the UN General Assembly, or even various national legislative documents, there is a sense of deep concern with this issue.

International Governance of AI

Discussions on governance of AI revolve around questions of framing any potential regulatory mechanisms under the umbrella of international law and the principles enshrined in the UN Charter. Using that foundation, exploratory efforts into AI governance mechanisms are also studying how previous mechanisms governing new technologies were introduced, and how they were received by member states. The goal of establishing such mechanisms is not only to find the best legislative phrasing, but also to secure as broad a support base for it as possible.

Because of the fundamentally different nature of this technology compared to anything that has come before, it has become clear that replicating existing mechanisms will be an exercise in futility. AI’s rapid development and disregard for boundaries requires a governance approach that is effective, swift, and broadly accepted and supported.

Securing support for governance mechanisms across both advanced and developing nations could prove a challenge because of potentially diverging priorities. Furthermore, broadening the scope of governance to issues like security and armaments may further complicate matters as governments may be reticent to reign in the advantages gained through the use of this technology.

Challenges in Diplomatic Application

The potential applications of AI to diplomacy and international affairs are extensive, ranging from the automation of repetitive tasks like translation, to sifting through large amounts of data, to decision support, and predictive analysis to name a few. However, we must account for the fact that ministries of foreign affairs are bureaucratic institutions, and will likely behave accordingly.

While there are real concerns relating to the technology itself, a significant part of the reluctance of ministries of foreign affairs is likely rooted in the organizational patterns of behavior on both the macro and micro levels. On the macro level, there will be a tendency toward resistance as a result of the system wide changes required to incorporate the technology into existing operating frameworks.

The introduction of AI into operating guidelines will require additional training, changes to technical and security systems within the digital infrastructure of the organization, and additional logistical considerations in standardizing the use of the technology, and preventing the dispersal of classified information through misuse of the technology by personnel.

On the individual (micro) levels, there are compounding factors embodied in the combined fear of replacement by the technology, and the reluctance (particularly on the part of mid to senior level officials) to change the operational patterns to which they have become accustomed. In combination, these factors will present hurdles at the adoption stage in many organizations. Symptoms of these factors are already reflected in the concerns voiced by the Advisory Body on AI regarding potential missed opportunities resulting from reluctance to adopt the technology.

On the other end of the spectrum lies the issue of overuse of AI. Once the challenge of introducing the technology is overcome, and the inevitability of its presence becomes a de facto reality, the tendency will be toward overreliance and potential dependency on the technology. Over the medium to long terms, this will result in a potential de-skilling of personnel, and reduce the cumulative insights, wisdom, and nuanced understanding that diplomats develop over their careers in the field.

Closely related to the issue of overuse is the matter of the [mis]use of AI as a tool for blame avoidance. It is not uncommon for ministries of foreign affairs to wield blame as a substitute for accountability. If a problem happens, solving the problem sometimes takes a back seat to identifying whose fault it was. AI will present a unique opportunity to avoid blame (accountability) for faulty decisions. Rather than risk making a decision that can result in blame, it will become bureaucratically safer to use AI as an accountability avoidance mechanism. In turn, this will allow for potentially reckless decisions to be made without sufficient consideration, as a result of reduced accountability.

Further complicating organizational calculations related to the roll out of the technology will be the internal discrepancies within organizations. While the divides between countries and governments that will have access to the technology and those who will not has already been raised, the matter of intraorganizational discrepancies and its potential effects on ministries and intergovernmental organizations has yet to be fully explored.

Within hierarchical organizations, the skew against adopting new technology leans toward the top, with senior levels being more reluctant to adopt new systems in contrast with the junior officers who will be more likely to adopt earlier. With the advent of new technology, unofficial use of new technology seeps into systems from the bottom as happened with the internet, instant messaging, and social media among others. Waiting for the bureaucratic processes necessary for the official introduction and adoption of the technology is frustrating for junior staff, particularly if they see their peers from similar organizations putting it to good use. Widespread unofficial use of technology resulting from delays in adopting it introduces vulnerabilities into organizational systems. With AI, these vulnerabilities could potentially be exacerbated by the nature of the technology itself.

Therefore, in addition to concerns about the technology, and given these potential intraorganizational challenges, organizations, both national and intergovernmental need to be cognizant of the internal issues that they could expect to face, and be deliberate in their planning of the strategies on the use of AI. They should be aware of how it will be introduced to encourage safe adoption and use, and of how resistance to its adoption could manifest.

A Diplomatic Uncanny Valley

The Uncanny Valley Phenomenon was coined by the robotics professor Masahiro Mori to describe the hypothesized emotional response to the degree of resemblance of a robot to a human. It is the valley that lies between the positive responses to clearly inhuman robots and the positive response to near human robots. It is the space where robots are somewhat, but not quite, human in their appearance and movements, spurring revulsion.

The introduction of AI to the field of diplomacy and international relations may result in its early stages in something similar. Diplomacy has always been somewhat imprecise, more akin to an art than a science, relying heavily on human interactions, and the interpretations and understanding that comes from consistent and direct interactions between emissaries across the world. The human element has remained an inalienable part of diplomacy over the course of history, and as segments of diplomacy are gradually relegated to AI, the hybrid creation could eventually deprioritize the nuanced elements of diplomacy that rely on interpersonal communication.

The overreliance on technology and potential deskilling of diplomats and other professionals in the field could feed into this pattern. If left to progress without guidance, this pattern could create a hybrid form of diplomacy that lacks the nuance and balancing elements of human intuition and understanding that develops through interpersonal connections.

Consider as a simple example the difference in conclusions drawn by an AI that analyses the written and spoken output of a negotiation versus diplomats who understand the cultural context behind the words. In some cultures, it is considered impolite and borderline rude to say ‘no’ outright when engaged in discussions, and therefore would substitute it with euphemisms understood to convey the message or convey it via contextual cues. AI in this case could potentially fail to take into consideration these nuances and reach mistaken conclusions about the result of the consultations. While a simple issue like the one in the example is easily addressed through the development and training of AI, other more complex issues will arise over time.

Exacerbating this issue is that with the prevalence of AI, more output will feature AI generated analysis and recommendations, which will then be processed by another AI, initiating a cycle of AI feeding on AI input to generate its own output. Output generated based on AI generated input tends -for the time being- to deteriorate in quality, which could result in a devolving diplomatic discourse over time.

These considerations highlight a need for a deliberate strategy to use AI to augment diplomatic abilities rather than replace them. The matter of using AI for augmentation rather than substitution is already under discussion on national and intergovernmental levels, which is a promising step that should benefit from more in-depth exploration on organizational levels to mitigate the medium and long term risks associated with the overreliance, deskilling and depersonalization of diplomatic interactions.

Machina Ex Diplomacy

As AI gains traction in international diplomacy, it presents a complex landscape where governments and intergovernmental organizations are exploring ways to address concerns about regulation, control, and potential misuse. While AI offers promising enhancements in data analysis, decision support, and automation, significant challenges persist—such as the risk of overreliance, deskilling, bureaucratic resistance, and a diplomatic arena reduced to machine interactions.

The advent of AI in diplomacy offers both unparalleled opportunities and formidable challenges. Thoughtful governance, careful implementation, and a balance between innovation and tradition are crucial. The decisions made now will shape the future of global diplomacy, making it imperative for stakeholders to harness AI's potential while safeguarding the human elements that are integral to international relations.